In her seminal article, “To the Beat Y’All: Breaking is Hard to Do,” for the Village Voice (1981), Sally Banes wrote:

“It (breaking) is a way of claiming territory and status for yourself and for your group, your crew. But most importantly it is a competitive display of physical and imaginative virtuosity, a codified dance form cum warfare that cracks open to flaunt personal inventiveness…When you choose your moves, you not only try to look good; you try to make your successor look bad by upping the ante. That’s one way to win points from the crowd, which collectively judges.”

The early accounts of documenting and analyzing breaking encompass many of its values. Through Banes’ vivid prose, we glean the elements of breaking in its formative years, see how they were put together, and perceive dancers’ goals and motivation. We get the sense of context and community and how spectators were an integral part of the culture; they made the most important decision – of picking the winner.

The early tradition of crowd judging couldn’t sustain itself as the art form gained popularity in the United States and spread around the globe. With more interest from general audiences, the original enclosed-by-the-crowd circle (cypher) had to open to allow spectators to see the dancers. The proximity of participants and onlookers thus changed. Spontaneous street battles evolved into jams (in local gyms, community centers, high schools, and parks), and as media and various companies (e.g. Red Bull) built interest in showcasing breaking for large international audiences, more organized competitions started to appear. These formats called for more comprehensive judging.

When I first moved to the United States in 2000 and attended jams in Chicago, the typical panel of judges consisted of three breakers invited by the organizers. They were selected based on their skills and reputation – top dancers in their communities. The judges watched the battles and picked winners by simultaneously pointing towards them after all rounds were completed. The majority vote determined the winner; in case of a tiebreaker, an additional round was called.

Criteria on which judges made their decisions were not always clear and rarely communicated to spectators. The underlying awareness was that each judge had their own process of reaching the verdict and, possibly, mostly valued aspects of the dance closest to their own perspective and skill set. A typical distinction back in these days might have been footwork versus power. Waka—a member of the notorious Chicago Brickheadz crew— known for his risky inventive power moves and warrior attitude, once told me that he wanted to see daredevil difficulty-level moves in battles. “I come from the era (the ‘90s) of creating. That was and still is my high. That feeling of doing something crazier than someone else brings the honor. Battling someone for that person, not the judges, not the girls or 100 likes on Facebook. Being smooth is good, but I’m expecting more – some extravagant dynamics.”

“Music is the key. Heartbeat is a rhythm.” – Ken Swift

Circa 2010, in my conversations with Ken Swift – a second generation Bboy from New York City, an artist and educator keeping the early traditions of his neighborhood alive – judging came up on numerous occasions. Kenny has always stressed the feeling music gives him and going off when it hits him. In the evolved premeditated battle competitions, dancers can’t wait for their favorite song. They have limited time to complete their rounds to the music played by the DJ. That factor alone can affect the execution or create a discord, he told me.

Judges have a challenging job of watching and critiquing at the same time, “You have to be keyed in directly…so heavily to visually see everything that is happening and look down on a piece of paper at the same time”, explained Kenny. If you take eyes off the dancers to make a note, you may miss something. Judging is based on criteria presented by each country. Following these criteria might get confusing because of how words are translated and interpreted. For instance, “style moves” and “power moves” are terminologies, Kenny said, he couldn’t identify with. “I’m like… wait a minute, the moves don’t have any style. It’s a person who applies flavor to the moves. Do you mean that you do power moves that don’t have style?” In the end of the day, he continued, it’s my opinion. “If you asked me to judge, you respect me and my opinion, right?” It may seem easy, but for the Bboys and Bgirls it’s not that easy. They can get mad if they disagree with that decision.

Contemplating further the intricacies of the process, being human, thus subject to making mistakes, is another potential factor to consider. Kenny isn’t afraid to admit that he might have made wrong decisions. If we add a possibility of jetlag, which weighs on concentration and focus, we can start to ponder a variety of factors affecting the judging process. Long-distance travel affects people in different ways, but that element alone is important to consider as it has become tradition to invite ‘megastar’ breakers to judge overseas. It’s part of the lifestyle. When I asked Kenny how he sees the world, “from the airplane”, he joked. Traditionally, having big names on the bill makes events more attractive and legit. It also conveys respect for the “OGs” – the original and highly regarded figures in breaking who inspired thousands of dancers, organizers, and promoters around the world.

As I am making final edits on this article, Ken Swift is flying to Cyprus for the Break Free Worldwide’s Strawberry Jam (June 10-12) to give a workshop on the ‘Education’ day, and to judge on the ‘Competition’ day of a three-day long event. His commitment to sharing art and carrying New York City legacy hasn’t wavered. The breaking world continues to be inspired.

South Korea, R16 and O.U.R. system

One high caliber competition throughout the 2000s was the infamous R-for Respect and 16-for the 16 competing international crews (R16) in South Korea. The country was considered a breaking promised land during that time. The government, public and private sectors supported, sponsored, and promoted breaking. The dancers’ skills matched the hype. When I was packing my bags to move to South Korea in 2009 to do research for my master thesis, the official Korea Tourism Organization brochure featured breakers (alongside traditional Korean musicians) on its cover page. Inside a five-page pamphlet, another photo of Bboys captioned: “Korea hosts the world’s fourth largest breakdancing competition,” invited tourists to experience the new Korean phenomenon. One of the dancers in this photo was Dyzee – a Canadian Filipino breaker who lived in South Korea for nine years and developed the first largely known judging system for breaking.

Realizing early on that the money deficit in breaking negatively affected opportunities for dancers, Dyzee’s goal was to take the art form to the next level by making it a sustainable industry. He traced this vision back to a dream he had in which he saw a large stadium with a spotlight on a DJ and two crews of 10-20 dancers “going at” each other. No real-life competition at the time matched the one he saw in his dream, and Dyzee thought it possible; one of the conditions of making this dream a reality was a fair objective and unified judging system. “Every legitimate art form has some kind of a governing body or association that looks out for the best interest of the culture…The way you know something is a true art is if you know how to judge it,” Dyzee explained in his documentary Meet Our Bboys (2012).

He thought that the place to make breaking professional was South Korea – a trendsetter country in Asia at the time. Not afraid to leave his family, friends, and crew, and keeping in mind the greater good of the culture he loved, Dyzee moved to Korea and started working on his dream with Cartel Creative – a non-traditional producing and marketing company specializing in youth inspired urban culture events. The outcome was a judging system they called Objective, Unified and Real Time – O.U.R.

The system was an attempt to eliminate issues Dyzee and many others observed throughout the years, for instance, possibilities of judges favoring a certain aspect of the dance or their friends, not remembering the details of all rounds, thus not being able to provide constructive feedback afterwards, or the lack of explainable to general audience standards, which would help sustain their growing interest. “Sometimes it’s obvious why you lost, if you crashed or the opponent was clearly better, but sometimes you are a bit more equally matched…Currently, judging is a bit of a mystery”; any improvement would be a step up, explained a dancer in Dyzee’s documentary.

O.U.R. system combined five “perspectives” on breaking:

- Foundation (Confidence+Musicality, ex. footwork, suave, finesse…)

- Originality (Maturity+Artistry, ex. character, technique, concepts…)

- Dynamics (Difficulty-blow ups, tricks, speed, balance…)

- Execution (Confidence+Cleanliness, ex. perfection, style, rhythm…)

- Battle Tactics (Responding to the opponent)

Each battle round was scored by a judge assigned to their “perspective”. The winner would be the one who took most of the five categories or majority of points (1-5 per category, each category and value explained further in detail). The judge’s responsibility was to solely focus on that specific category instead of simultaneously evaluating all aspects, thus, possibly, making the job easier on the judges.

Some of O.U.R. system concepts and their organization can be compared to scoring college-level writing on rubrics, I’ve used for about two decades as an educator. If I was to only grade one category, say – ‘development of ideas’ on a 1-5 scale, it might become quicker and more efficient. My mind might fine tune itself to seeing and evaluating a specific element faster as opposed to dividing and keeping focus on every category simultaneously. But it’s also possible that seeing things in isolation obstructs the full view.

In any case, grading is a highly demanding mental task carrying tremendous responsibility. What’s easier in marking essays, as opposed to judging breaking, is that they are permanently laid on paper. A teacher can read as many times as needed or go back to certain components the next day to confirm the previous decision. Judges can’t do this in breaking. Rounds happen once and fast. The O.U.R. system took this into account through scoring in real time. It also considered an audience by displaying ipad-recorded scores for spectators to follow, which helped them understand and stay in the game. The system allowed freedom (no checking boxes), valued all “perspectives” (by unifying and treating them equally), and provided transparency by collecting statistics, so there was a way of tracing back scores. The system was globally launched in 2010 and utilized at all R16 Global Series events.

Although it took years of conceptualizing, creating, revising, and implementing the system for the good of the community, it was met with skepticism, criticism, and rejection. Some thought breaking wasn’t a sport and didn’t need a judging system; some thought that the system would change the art form by making dancers fit into the criteria; some thought Dyzee was doing it all for personal gain.

Outbreak Europe 8 and Catch the Flava Breaking Camp 1 in 2012

During the combined Outbreak Europe 8 competition/Catch the Flava 1 breaking camp in Slovakia (2012) with Ken Swift (East Coast), Kazuhiro (Japan), Freeze (Sweden) and Ivan the Urban Action Figure (aka the Wolverine of Breaking), the O.U.R. judging system was the most popular topic among the attendees. The evening’s panel talk, as an integral part of the weeklong camp, provided an opportunity to explore the fifth element of hip-hop – knowledge. In Banska Bystrica’s dimmed auditorium spotlighting the breaking legends, some camp attendees relentlessly voiced their doubts regarding Dyzee’s efforts. The hosts—members of Polskee Flavor crew—kept growing increasingly impatient with such a one-directional train of thought. Bboy Cetowy tried to redirect the crowd’s focus, “C’mon, different topics, not just judging”, he pleaded. But the participants weren’t hearing it. At some point, a United States Bboy sitting in the audience proposed a vote to decide whether we were in favor or against the system. This is when Ivan, in his usual shrewd perspicacious on-one-breath kind of way, exclaimed: “NO! We’re not gonna do that. We love Cartel (Creative). We respect Dyzee.” Kenny, Freeze and Kazuhiro nodded in agreement. That put the end to the crowd’s polemic. Nobody was going to take it up any further with the Wolverine.

On Dyzee’s website (accessed in 2022) “education of both participants and fans” is listed as a major objective in developing the system. The Banska Bystica experience illustrates how hard that task was.

Red Bull BC One

Simultaneously, other competitions continued throughout the world. One of the most notable one-on-one international championships is Red Bull BC One World Final. Started in 2004, this main event features the top 16 Bboys and Bgirls competing for the world championship title. Regional finals are held for North America, Latin America, Western Europe, Eastern Europe, Middle East, Africa, and Asia. The winners of each region punch their ticket to the world finals. The Red Bull BC One Golden Belt is one of the most desirable trophies in breaking, and a panel of five judges decides who gets it. Local and national Red Bull cyphers are judged in the ‘traditional’ way – an uneven number of judges, on the count of “3, 2, 1” point to the winner after all rounds are complete. World finals employ a similar format with one difference; instead of pointing, the judges hold up name cards revealed one by one, thus increasing the audience’s anticipation.

In an article published on Red Bull BC One website (Adelekun, 2021) “eight of the most common criteria judges use for breaking contests” are musicality, foundation, difficulty of movement, character and personality, style, execution, originality and creativity, and rounds composition. Numerous other articles presenting interviews with Red Bull BC One judges asked them for their three top criteria. Sometimes the views intersect; other times they differ.

Buenos Aires Youth Olympics 2018 and Paris 2024 Olympic Games – Threefold/Trivium Values Judging System

In 1983, Michael Holman, the New York City-based artist, writer, filmmaker, musician, and the manager of the New York City Breakers—a legendary ‘80s crew, which impressed him by their athleticism and power moves—predicted and openly voiced his visions of breaking as an Olympic discipline. He wasn’t the only one. These visions became a reality in 2018, as the International Olympic Committee (IOC) included breaking in the Buenos Aires Youth Olympics. After its successful run, adult breaking was chosen to be showcased on the Olympic stage in the upcoming Summer 2024 Paris Games.

Nearly four decades since Holman first made his statement, communities around the world are in the process of creating an infrastructure and governing bodies to forge a path for national representations to compete in the Paris 2024 Games. A comprehensive judging system with certified judges and educational initiatives is a crucial link in preparing for the Olympic moment.

The Trivium Values judging system—first used in Youth Olympics qualifiers and the Youth Olympic Games in 2018—was mainly developed by Niels Robitzky (aka Storm) from Germany and Kevin Gopie (aka DJ Renegade) from the U.K. Dominik Fahr and the teach team at and8.dance invented the interface. The Threefold/Trivium system will also be used in the 2024 Paris Games.

As more Breaking for Gold qualifying events and championships emerge globally within the scope of the World DanceSport Federation (recognized by the IOC as the world governing body of DanceSport – the term coined in the early ‘80s to encompass both athletic and artistic aspects of dancing), an interest in the judging system employed in these competitions also rises.

USA Dance and Breaking for Gold USA Threefold Judging Seminar

Responding to this growing need for educating all involved, USA Dance (the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee-recognized DanceSport organization in the United States) and Breaking for Gold USA (its official breaking division) held an open-to-the-public Threefold judging seminar, on March 13, 2022. The seminar was followed by an exam for those interested in becoming certified adjudicators, eligible to judge Breaking for Gold USA sanctioned events. The lecture was delivered by no other but Kevin Gopie (aka DJ Renegade) – half of the dynamic duo of the masterminds behind the system.

A skilled and engaging lecturer—DJ Renegade—in five and a half hours broke down the philosophy, rationale, and technicalities of the complex intuitive model, he and Storm called wholistic. “Whole is always more than the sum of its parts. As such, judges need to look at the whole performance with all of its content, its aspects and how it unfolds, the criteria, and the hierarchy,” Storm explained in 2018.

Coming to the decision as to what constituted the whole was a process of selecting words that described breaking, (started by Gopie, Storm and a few others in 2012.) Out of the initial 150 words, 15-20 were left; 17 of these words were then grouped into families and domains. Such tasks can be complicated because people may see things differently. They may disagree where words belong as human thought structuring our language is in its nature complex and, many times, culture dependent. Some concepts can belong to more than one category, and categories may overlap. Gopie stressed that the developed model was not a closed system but forever open to changes and contributions; as breaking evolves, so can the model.

Breaking is more than a sum of its moves; it encompasses intent, motivation, goals, benefits, individuals, interactions, teams, and community. Physical movement—the shared act of dance— is the observable dimension of the culture and a communicative behavior within itself. Thought, however, although not directly observable underlines the linguistic and physical behaviors. The three constantly influence each other.

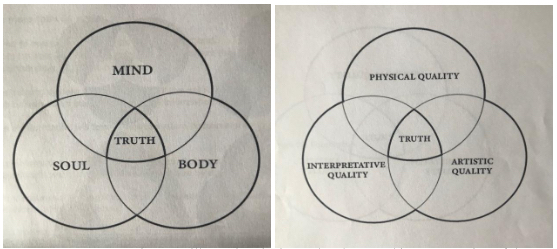

Judging such a multilayered act is challenging. For the system to be successful, it must be true to the culture in its entirety; otherwise, we’re risking compromising its crucial components. If we look back at the description of breaking by the late Sally Banes (one of the first and most beloved scholars of breaking) at the beginning of this paper, we can decipher the following components: physical quality (“competitive display of physical virtuosity”), imagination (“imaginative virtuosity” – a quality of the mind), intent, individuality, team (“a way of claiming territory and status for yourself and your crew”), the goal and means to achieve it (“you try to make your successor look bad by upping the ante”), competitive aspect, and the importance of judging.

Congruent with multidimensional aspects of breaking, the strength of the Trivium system lies in its acknowledgement and equal distribution of values within its three main domains:

- Mind – the Artistic Quality (Creativity and Personality)

- Body – the Physical Quality (Technique and Variety)

- Soul – the Interpretative Quality (Performance and Musicality)

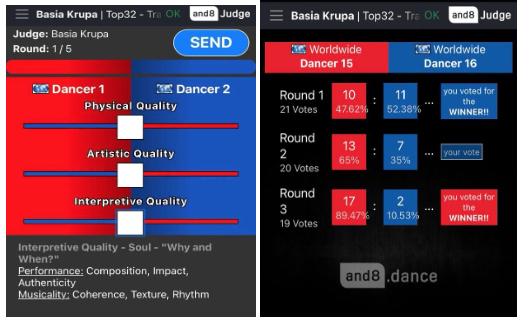

The digital interface with faders assigned to each of these qualities (three for Threefold —Artistic, Physical, and Interpretative; six for Trivium– including all listed above subcategories) allows judges to react to imbalances in these domains as they directly observe two dancers. The “truth”, thus fair and objective decision, lies in the middle. “Investigate for Truth”, read the seminar notes penned by Renegade and Storm.

The Trivium model might be complex, perhaps challenging to grasp at first, but it is also quite brilliant, deeply considered, and meticulously put together. It accounts for many issues the scene has been faced with throughout the years.

One such issue, identified by Gopie, is hiring people to judge based on their performing abilities, reputation, or connections within the community, instead of their ability to judge consistently and fairly. Because someone is a great dancer/performer does not necessarily mean that person will be a solid and effective judge.

Another issue is conscious or unconscious bias, such as:

- Novelty – liking to see something new

- Affiliation – wanting to see a friend win

- Familiarity – prior experience with the dancer

- History – what the dancer is known for

Trivium accounts for these possible biases by only aiming at the performance at hand and against a particular opponent in the moment, in this battle.

Judging in direct competition is most likely the biggest difference between Trivium and other scoring systems – whether in sports or in school. To give an example, figure skating is judged based on predetermined standards. The competitors are required to include certain elements in their routines; these elements are given point values based on a ‘perfect’ iteration of that element in each judge’s head. In school, teachers using grading rubrics have a perfect assignment model to reference in their mind. They assign grades by marking against this model of perfection.

Because breaking values freedom of expression, checklists of moves/tricks and standards of perfection do not exist. If they did, they may make breaking stagnant by forcing dancers to fit into categories, then shift their focus onto perfecting moves while possibly sacrificing musicality or transitions – both crucial elements in breaking. Breaking has shown such a high level of continuously increasing physical ability, even a perfect 10 may not do it justice. What if a dancer is a 10, but the next one happens to be better? What if a dancer is a 10, but next year excels even further? “The beauty of breaking is that we are not sure in which direction it will really go”, remarked Renegade.

I have once experienced limitations of scoring in isolation when asked to evaluate breakers on a scale 0-10 without seeing the opponent. The dancer in a video clip was clearly competing against another; however, I could not see the opponent. It was problematic to assign values because I wasn’t sure whether a 10 should be awarded to one of the best dancers breaking has ever seen or the highest ability in this particular dancer’s level – ‘beginner’ or ‘intermediate’. This reinforced the realization that, within the culture, we are used to making decisions by seeing breakers in battles – the natural format since its inception, development, and continuous evolution.

If there are any misconceptions about breaking equaling difficult tricks, a holistic most-important-values-encompassing judging model might be a good chance to prove to the large audience that it is much more.

As a tool recording the natural ‘language’ of breaking – dance, the Trivium model is thus descriptive, not prescriptive. It allows judges to look at an individual expression of breaking without prescribing its exact structure, form, or components/specific moves. This does not mean that breaking is ‘anything’; it means that the model allows and values natural free expression within the style. “The winner should be the one better representing the dance style of breaking,” explained Renegade.

Part of the seminar was getting the feel of the crossfaders (one per each quality in the Threefold system). They are precise and sensitive. After each round, a judge presses ‘send’, and the interface readjusts to its original position for the second round. The system does not allow tiebreakers; it won’t accept the score unless at least one fader has been moved. It also collects statistics for future reference and data analysis. If a judge keeps consistently scoring outside the majority, it opens room for discussion. In case of close rounds, dancers seeking feedback have something to fall on.

After submitting the votes, we discussed our rationale. Renegade included his own thought process in arriving to a decision. We compared similarities and discrepancies. Similar benchmarking sessions were discussed as were regularly scheduled meetings among the certified judges who constantly work on sharpening their judging knives.

And once again, we do the same as teachers. Even a well-crafted rubric yields different final scores dependent on a teacher. A total and precise agreement isn’t necessary, but in efforts to provide fair scores to students and ensure the highest standards, such sessions are a norm in the education field. Because grading is so mentally taxing, it is most likely my least favorite part of teaching; however, it is also necessary. And so is judging breaking.

Acknowledging the challenges and restrains of judging, Renegade noted that it might be the least desirable job in breaking, “You’re given a huge responsibility and subject to scrutiny. You’re not able to just kick it with your friends. It’s an intellectual challenge, not a physical one.” Realizing this might be the first step to appreciating and valuing individuals who take the challenge on. The seminar notes included strategies to prepare for events. Some of the advice was unpacking the specific criteria within the “mind-body-soul” mind map, staying relaxed, hydrated, focused and bias free.

Emmanuel FoX, a dancer, youth Olympic coach and Threefold/Trivium certified judge did just that on his flight to Paris to judge his first Trivium scored competition – the WDSF World Championships in Paris on December 4, 2021. “I was a bit nervous because I was thrown into the deep waters right away. Passing the exam shows you understand the system, but it’s the practical application that confirms you can really judge,” explains FoX. He wasn’t sure how he would do with all six faders, but as soon as he started scoring it quickly became automatic. “I was in the zone, no distractions, and doing it fast. I wasn’t using all the faders. I think I used four max. You don’t have to use them all; that’s the beauty of it – looking for imbalances and recording them.” Aside from technicalities of the system, judging carries a lot of responsibility. FoX emphasized, “You’re dealing with people’s dreams, time, hard work, blood, sweat, and tears. You cannot be on that seat because you want the best seat in the house. It’s a job and it’s not an easy one. You must abide by the code of ethics – no talking to others, no consulting decisions, no phone, no drinking. If you’re not in a reasonable mental or physical condition, you can’t judge. It’s not a party; it’s work.”

Renegade stressed that the Treefold/Trivium system is a tool – a recording device, which does not force anyone to judge in any specific way. FoX reiterated that the tool is only as good/objective as the person using it. Renegade restated the module’s descriptive value by saying: “Don’t try to fit the module into you; you fit into it.” If we sit with this sentence, we can recognize that there is a big difference between the two. If a breaker makes it through and up the top ranks, they embody the values whether they choose to consciously dissect them or not. Fitting into the module is thus natural and stresses the dancer’s agency as a creator expressing the style in their own unique way.

If we go back to how it all started— to the heart and soul of competition, the spirit of entering a battle to prove to oneself and others and coming back a better version of oneself— standing and moving in that ring, regardless the outcome, is quite possibly an already fulfilled mission.

If you’re true to yourself, deep inside, you know if you won… In the words of an old friend and a breaking icon, “If you did your best, no one can tell you that you lost.”

Basia Krupa

Basia Krupa is a writer, dancer, linguist, university instructor, and breaking advocate currently residing in Chicago, Illinois. She holds a double master’s degree—in Culture and Education—from her native Kraków, Poland and in Linguistics—from Chicago, Illinois. She has also lived in South Korea and China, where she researched breaking and wrote a master thesis combining her findings.

Basia is happy to connect via IG @breakin_andbecoming

References:

Adelekun, E. (2021, September 9) 8 of the most common criteria judges use for breaking contests https://www.redbull.com/dk-da/judges-criteria-breaking-competitions

Adelekun, E. (2021, October 27) These are the judges of Red Bull BC One World Final and their criteria https://www.redbull.com/int-en/red-bull-bc-one-world-final-judges-criteria#4-round-for-round

Adelekun, E. (2020, June 8) Find out how the Red Bull BC One E-battle 2020 will be judged https://www.redbull.com/ca-en/red-bull-bc-one-e-battle-judging-criteria

Banes, S. (1981, April 10) To the beat Y’All: Breaking is Hard to Do, Village Voice, Reprinted in Banes, S. (1994) Writing Dancing in the Age of Postmodernism (pp. 121-125). Wesleyan University Press, Published by University Press of New England, Hanover

“Dyzee Diaries” (accessed May/June, 2022), https://www.dyzeediaries.com/portfolio-items/our-system/

Saussure, F. (1959) Course in General Linguistics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Videos:

B-Boy & B-girl Dojo. (2019). Renegade: Why Do We Need a Judging System

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mr57ZrvAfa0

Dyzee Diaries. (2011). OUR System- For B-boys By B-boys (How it works) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fqlIk-49e8U

Hiski, Hamalainen. (director). (2012) Meet OUR Bboys- A Street Soul TV Documentary https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9jKkNEjTgbg

Stormdance. (2018). On judging 08 the Trivium https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5jp2rxexFcc&t=0s

Stormdance. (2021). Trivium System Animation https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZoFaO7g6Jwg

Personal Communication:

Waka (2008, 2015) Chicago

Ken Swift (2010) New York City

Emmanuel FoX (2022) Zoom

Kevin Gopie (aka DJ Renegade) (2022) email